LOST GRIDS, OR HOW TO EXPLAIN DIGITAL MEDIA TO A DEAD SOCIALIST >

[2018 - Present]

< Short Story >

The project comprises a generative mechanism built from an artistic misuse of digital code. A two-step: Images and texts are appropriated from the cultural archive and coupled to form networks of loosely associated image-text pairs. A text is then selected from each network and entered directly into the underlying code-bed of the image with which it has been paired. A rupture results in the image, and from this glitch a grid is extracted and then scaled up. The relationship between grid as surface and network as depth forms the project's conceptual core:

The essence of surface and depth:

incommensurability;

that is to say,

radical ornamentalism and radical obscurantism.

The Lost Grids project to-date has yielded prints, artist books, video installations, and performance-based work (samples below).

NOVELLA_DEL_GRASSO (2023)

[Fourth of five Lost Grids]

Source Material >

Image-Text Pairing: a perspective drawing (Andrea Pozzo) and a tale of Filippo Brunelleschi

Anamorphic perspective drawing (Andrea Pozzo, 1693)

[Perspective Experiment]

After Filippo Brunelleschi

(Early 15th Century)

« Manetto, known as il Grasso, was prosperous and good-natured, but one day had the misfortune of incurring Filippo’s ire after missing a social gathering. Never one to resist retaliation, Filippo resolved to exact his revenge for this perceived slight by persuading a wide cast of characters to convince Manetto that he had metamorphosed into someone else: a well-known Florentine named Matteo. »

Ross King, Brunelleschi’s Dome (2000)

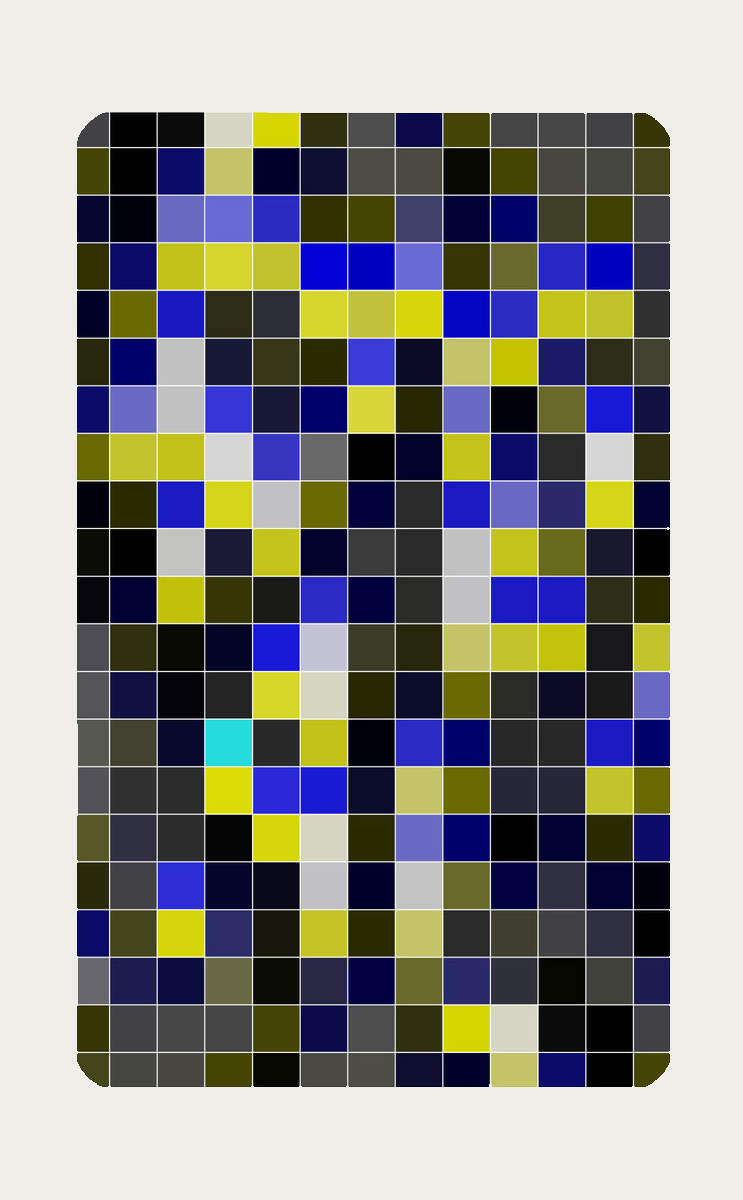

Novella_del_Grasso [resulting manifestation of text-image intervention as a grid print] >

Digital print mounted between glass and aluminum

60 cm x 85 cm

LOST GRIDS >

Project manifestation as an artist book

22.5 cm x 30.5 cm

Enclosure for six booklets, one for each «lost grid» and a sixth presenting the loose prints (in A3) of the five grids (slide show below).

SLIDE SHOW OF LOST GRIDS AS LOOSE-LEAF PRINTS >

Scroll over for titles

SAMPLE INTERIOR PAGES FROM BOOKLETS >

HEXBOOKS >

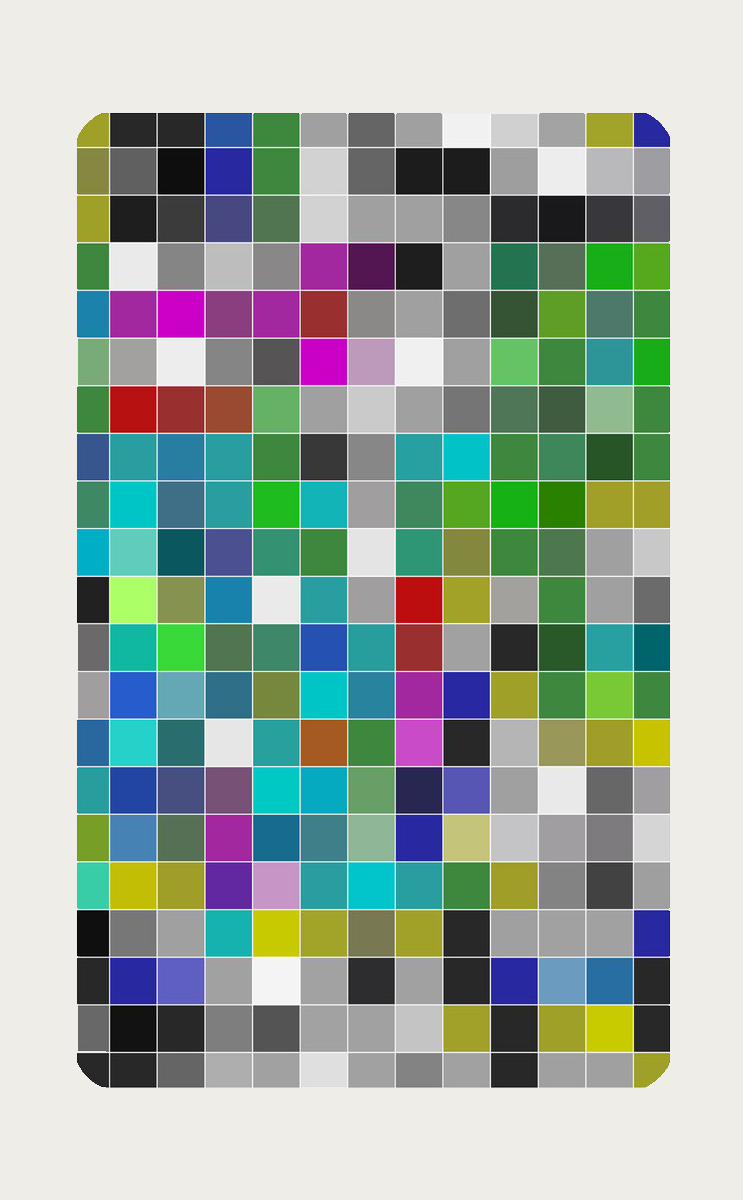

The underlying hexadecimal code of the resulting Lost Grids have been formed into «Hexbooks», each made of 500+ pages of loose-leaf sheets. With these books, some preliminary experiments with performing the code have been hatched: Hex Performance.

Project manifestation as 500+ page books of hexadecimal code.

SELECT-ALL >

In this manifestation (see below), the hexadecimal code is presented in a linear format without line-breaks, abstaining from the necessary discontinuities found in code production, paragraphing, and poetic enjambment. One here encounters the impossibility of reading and viewing at the same time – that is, code as text and as image.

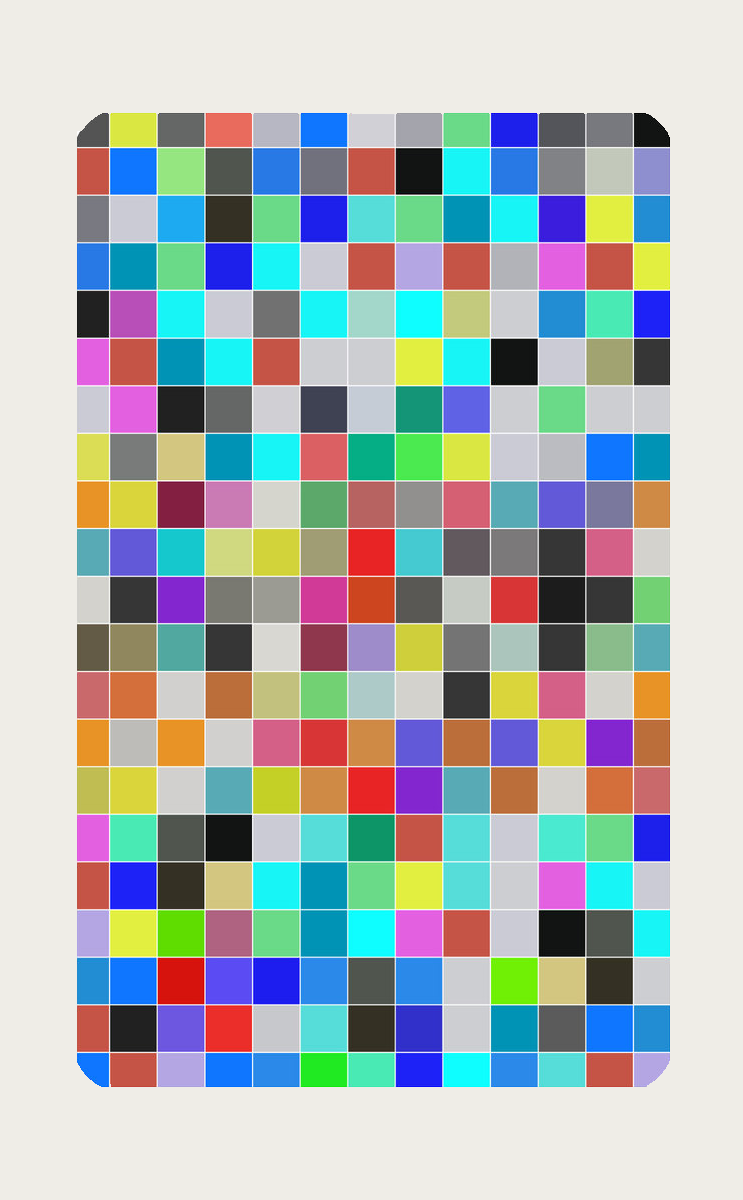

SWATCHBOOKS (videos) >

After the grid squares are organized as a digital book, using the phi ratio for design, these books are then converted into video loops that shuffle through the variegated pages.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Marx's Beard> swatchbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Arrival of the Train> swatchbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <The House Is Black> swatchbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Novella del Grasso> swatchbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Portolan Orifice> swatchbook.

HEXBOOKS (videos) >

Below are videos of the 500+ page Hexbooks (comprising the code that undergirds each grid) scrolling as videos.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Marx’s Beard> hexbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Arrival of the Train> hexbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <The House Is Black> hexbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Novella del Grasso> hexbook.

Transformed from Lost Grids: <Portolan Orifice> hexbook.

< Longer Story >

The Lost Grids project comprises, first and foremost, a generative apparatus for producing and juxtaposing two incommensurate planes: a plane of associations forged by citing and pairing pictures and statements from the cultural archive and a plane of corresponding visual surfaces produced by intermixing these citations through a creative misuse of digital code.

The first plane is made up of curated networks of image-text associations organized into thematic sets. Each set’s coherence ranges from argumentative assertions to ideas that drift in and out of oblique and problematic linkages. In this way, each associative ensemble presents a connective logic intended to mimic without credibly delivering the lucid and over-reasoned bond of illustration or explication. The overarching aim is to loosen, recalibrate, and overcharge the valences of each element and to assert their altered potentiality within a larger associative network in which the elements have been positioned.

The second plane consists of visual surfaces that take the form of variegated grids. Each grid – neither text nor quite image – is produced by a process in which a text – philosophical, poetic, critical, or quotidian – is selected from the associative network and then entered directly into the underlying code-bed of its corresponding image. A disruption in the image consequently results, and out of this visible glitch a palette of pixel patterns is assembled, from which the final grid is ultimately created. Standing opposite the grid as its progeny, this privileged image-text pair, plucked from its network, indicates the single point of contact with the larger associative network, which otherwise remains aloof from the colorful grid. Such is the wide interval between the parallel series of grids and corresponding networks that presents the project’s conceptual core.

And so goes the ongoing generativity of the Lost Grids project – a detour from the flatbed picture plane and a dubious nod to the commodity fetish – as it follows the guiding principle: The essence of surface and depth: incommensurability; that is to say, radical ornamentalism and radical obscurantism. The initial exhibition of the work as prints was installed at the Werner Thöni Artspace (Barcelona) dividing the gallery space between the grids (printed on polycarbonate sheets) displayed along one wall and the image-text networks out of which the colorful grids were produced, along the other. The physical gap between these two corresponding series presented the locus of viewing in which one must alternate between the simplicity of ornamental surface and a complexity of depth.

The ongoing Lost Grids project branches off into manifestations beyond wall prints: into books, video loops, code images, and performance-based work. Two sets of boxed books are currently being designed: One set of five books lays out the grid designs in folio format that orders the 273 colored squares of each grid (13 x 21) into the bound sequence of a book. The second set is made entirely from the hexadecimal code of each grid (upward of 500 pages each); the books are left loose-leaf (see below) such that each page of code can be lifted as an individual digital drawing. The code books are accompanied by a pamphlet including prints of the grids, the image-text networks for each print, and an artist statement. Both sets of books have been transformed into video loops (see Sets 1 + 2 below) designed for installation format. In another formation, the textuality of the code in its pure linearity is manifested as a single illegible line. Finally, the code will be developed into two sets of performance-based works: one that presents performative recitations of the hexadecimal code, the other that transforms the code into choreographic prompts for staged dance performance.

Early Project Notes (2017) >

The Lost Grids machinery begins its series of productions with picture citations loosely associated with hair: Marx’s beard, Ana Mendieta’s cosmetic hair implants, Julia Pastrana (the «bearded lady»), contemporary beard fashion, the 1967 Patterson/Gimlin Sasquatch film, Pierre Huyghe’s «Untitled (Human Mask)», Jeff Koons’ «Michael Jackson and Bubbles», the Bolivian military’s hand stroking the head of Che Guevara’s corpse, Joseph Beuys’s intimate handling of the dead hare in «How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare», Méret Oppenheim’s fur cup «Le Déjeuner en fourrure», a hairy exchange from An Andalusian Dog, Courbet’s «Origin of the World».

From among the texts paired with this set of pictures, an excerpt from the Situationist critique of revolutionary ideology is pasted into the underlying code of John Mayall’s widely published photographic portrait of Karl Marx. This image presents the spectacle that teaches if we know anything at all about Marx and his ideas it is that the man had a beard. Whence the title of this piece: Marx’s Beard.

The Lost Grids project intersects with my 2017 solo exhibition, IRAN|USA (Saint Mary’s College Museum of Art. Included in this show of video installations, films, and prints was a piece entitled The House Is Black, for which I devised the conceptual digital strategy outlined here. This print began with an iconic photograph of the Shah of Iran Mohammed Reza Pahlavi’s lavish, gold-laden bedroom. The photograph was chosen based on its iconic value, its depiction of the intimate and aesthetic dream-space of a brutal dictator, and the oblique reference it makes to the long-standing policies and geopolitical interests of the United States, whose financial support helped to bankroll the “spendthrift and ceremonial life” of the Shah. Into this photograph’s underlying code I directly entered a set of cultural texts [Figure 3] – including brief passages from press clippings, critical theoretical tracts, memoirs, a will and testament, and literary works – all selected for their literal and metaphorical resonances with the image. Most prominent among these intervening texts was the translated poetic script of Forough Farrokhzad’s 1962 experimental documentary, The House Is Black, an important work in film history that celebrates the residents of the Bababaghi Hospice leper colony in the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. The print I made and named after Farrokhzad’s film presents the prototype for the Lost Grids project and has been reworked for the new series.

The central maneuver of the Lost Grids project positions this planned work within the field of conceptual art. Integral to the work’s meaning, the creative process by design will result in a set of images whose decorativism, while it alludes to the history of the grid in art production, simultaneously refrains from providing any representative image reflecting the scope of the work’s meaning. The Lost Grids project here deliberately departs from a traditional method of either figuration (analogic representation) or montage (picture-text layout, ekphrasis or ut pictura poesis) and in this way extends and transforms my long-standing interest in questions of illustration, theoretically conceived within an image-word problematic (a focus of my PhD dissertation and much of my art practice).

Project Implications >

For me, the implications and stakes of this planned new work emerge at the level of object, production, and form. At the level of object, the project’s unrelenting reference to a central structuring absence within the artwork resonates with questions across several disciplines: the post-Kantian “object” within contemporary continental philosophy (speculative realism or object-oriented ontology), the structure of the Unconscious in psychoanalytic thought, and the theory of “commodity fetishism” in Marxian discourse. At the level of production, the Lost Grids respond to widespread assumptions about the expediency and corrective power of digital technology. The project’s ostensibly counter-productive use of technology aims to foreground a question of work, implicitly and explicitly creating associations with positivist or functionalist notions of working systems, the political-economic sense of labor, the psychoanalytic concept of dream-work, and the artistic sense of the work of art. At the level of form, the project endeavors to reflect on the Western tradition of the visual grid. This art-historical trajectory spans the two dominant functions of the grid in Western art, ranging from the utility of the Renaissance “perspective machine” – a grid-shaped apparatus deployed as an aid for the proper geometrical rendering of three-dimensional space – to the emergence of the grid as visual subject matter in the flat, abstract gridded canvases of modern and contemporary art. In contrast to art theorist Rosalind Krauss, who has famously argued for an oppositional politics between these two uses of the grid, I am interested in conceptualizing the continuity of the two aesthetics in relation to the additional status of the pixel grid that undergirds all digital imagery.

Starting Point >

To offer a sense of the work in progress, here are two pieces under development:

Marx’s Beard

John Mayall’s widely published photographic portrait of Karl Marx will provide the base image for producing this grid print through the process of poetic hacking. If the public – at least the general U.S. public – knows anything about Marx beyond the fact that he was one of the authors of The Communist Manifesto it is (thanks to the Mayall portrait) that the man had a beard. My interest in this iconic photograph is the cultural status of Marx’s beard as an inverted form of the commodity fetish. In the extensively cited section of Capital, “The Fetishism of Commodities,” Marx articulates a two-fold insight into the character of the commodity: the commodity’s form elicits fascination from its beholder while at the same time materially repressing the conditions of labor that produce the object. The spectacle of this iconic facial hair might be said to symbolize the very separation between Marx’s writings and the contemporary moment; crudely put, the iconicity of the photograph signals a preference for seeing the recognizable, impenetrable beard of a by-gone radical over grappling with the labor (and potential contemporary relevance) of that radical’s intellectual work.

Marx’s argument makes its way into my project as an insight into the aesthetics of the object in capitalism. As the inaugural piece in the Lost Grids series, Marx’s Beard points recursively to a central inspiration for the project itself. The unmistakably superficial, decorative, almost bathroom-tile appearance of each Lost Grid presents a veritable wall behind which there lies an irretrievable image, an artistic process, and a call for the viewer to enter the conceptual universe of the work. Pointing a humorous finger at the spectacle of the beard, I will enter key passages from Marx as well as Guy Debord’s 1967 Situationist tract, Society of the Spectacle, where the latter text paradoxically explores the “spectacularization” of politically radical ideas in the service of capital. To put the beard in both semiotic and historical context, additional texts will make their way into the underlying code of the Mayall portrait of Marx: a short typology of beard and grooming styles; sentences extracted from biological, anthropological, and cultural studies on beards; a few details from the poignant biography of Julia Pastrana (a “bearded lady”); and an excerpt from a medical article on Congenital Hypertrichosis Lanuginosa.

L’Arrivée d’un Train en Garde [sic]

Auguste and Louis Lumière’s renowned 50-second film sequence, L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1895), is known as one of the first works of cinema and also known, by urban legend, to have caused its first audience such fright that the group leapt from their seats. Whether based in myth or fact, the common presumption of this reaction’s primitivism, from a contemporary standpoint, overlooks a relevant facet of – if not this landmark screening – then the illuminating possibility of such a reaction and what it could suggest about the disruptive nature of images as such. The works of both Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan account for the traumatic kernel of the imaginary, suggesting that trauma emerges not when the imaginary is disrupted by an intrusion of the real but rather that trauma is already a structural feature of the imaginary itself. I’ve explored this distinction previously in my art practice. My short film CAMP (2011) opens by citing the Lumière film and synthesizing the exactly aligned movements of the Lumière train and a train in Alain Resnais’ film, Night and Fog. Thematically, CAMP investigates in part the coincidences of cinematic and holocaust technologies of transport and here begins by marking a traumatic juncture within the cinematic image. By shifting my use of the Lumière material from a time-based medium to a static medium (in the Lost Grids), I want to stress that it is not so much the train’s movement that carries a startling potential for an audience but rather something already in the nature of images themselves.

My planned print, L’Arrivée d’un Train en Garde [sic], will be based on a frame extraction from the Lumière film where the train’s engine appears to move hors champ, out-of-frame – the presumed point of disturbance for the inaugural audience. I will intervene into this image’s code with various texts that problematize the assumed relationship between trauma and image, real and imaginary, including an important excerpt from Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (specifically the dream in which a father’s dead son haunts him: “Father, can’t you see I’m burning?”). The textual materials include also accounts that capture the instability of a set of controversial iconic photographs, including the video documentation of the police beating of Rodney King and the corpse of Che Guevara, both of which ended up contributing to the exact opposite effect anticipated by their producers.